It’s not beyond reason to think that no matter where one lives Hitchcock’s name is one of the best known among filmmakers, since he was lionised in the fifties by French critics who urged that this work be reappraised. On the cusp of modernity many newcomers advocated for him, alleging he had outpaced his contemporaries. Later on he spurred an ever increasing array of books, articles, conferences and quotes, so that over the years his stylized films became compelling watching by the majority of moviegoers from all walks of life.

In truth, he never spearheaded an artistic movement nor did any groundbreaking independent film, rather he pled for film as entertainment, though he was very aware of the leading-edge in the field of art. In hindsight he is considered to be one of the most influential filmmakers because, in stark contrast with the seeming flimsiness of the plots (for instance, North by Northwest is a cock and bull, if highaly enjoyable, screenplay), he was prone to hiding the breadth and depth of the stories he had told in order to remain in the good graces of the audience. He preferred not to be highbrow even though he had a wide-ranging mind and was well-known for his wit.

The exhibition, Hitchcock, Beyond suspense, held in the Espacio Fundación Telefónica (Madrid) is said to be the very first in Spain dedicated to Sir Alfred Hitchcock (he was knighted four months before his death).

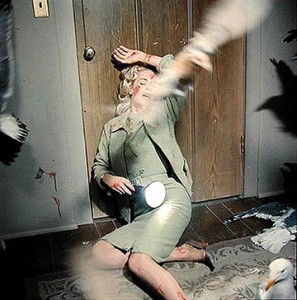

His curator Pablo Llorca, a filmmaker himself, decided to divide it into several chapters. The first room called “Icons” offers the visitor a series of blow-ups he took from frames of Hitchcock’s films. If memory serves the razor comes from Gregory Peck’s hand when he goes downstairs in Spellbound (1945), the rope held by James Stewart from Rope (1948), Kim Novak’s bun from Vertigo (1958), Janet Leigh’s eye from the end of the “shower scene” in Psycho (1960), and the glove stained with blood after Tippi Hedren has been attacked by a seagull in The Birds (1963).

Doubtless this is an accurate way of encapsulating the uniqueness of his vision, not to mention the fact that he felt attracted to abstraction and managing to include it in commercial movies. From the start he attempted to produce an immediate emotional effect at the prospect of blurring boundaries between genres and structures, and perhaps above all of triggering our unbridled imagination. David O. Selznick – producer of Gone with the wind – hired him to shoot the famous Rebecca (1940), told by a dead woman from beyond the grave. According to many people this challenge helped him to stretch his wings as a director.

Some people believe that from that point on the British director lost in the United States his genuine gift to use a mannerist style. Speaking for myself, unlike many viewers I never held Psycho in high esteem due to its highly derivative and mechanical direction, but he did nonetheless produce a large number of unforgettable scenes.

Hitchcock was accustomed to say: The script is written, now we just have to add the dialog. To him the purpose of a director was to give the viewer a cinematic experience. He was once asked what the best quality was for a filmmaker. He replied: to have an excellent visual memory. We can guess he kept track of memories he used, whether consciously or not, when he was preparing the storyboard of a shot. Further on, in the exhibit, a room labelled “Hitchcock and his time” reminds us of the roster of artists who arguably influenced him, namely, Picasso, Dalí, the Whitney Brothers, Len Lye, Julio Le Parc, Balenciaga, Christian Dior. It is very true. Suffice it to say that the dream sequence of Spellbound was designed by Dalí.

In thir respect the visitor should be sure not to miss the storyboard of sequences, like the Statue of Liberty scene taken from Saboteur (1942) and to the timing diagram of a sacne from Torn Curtain (1966). But I am afraid the sequence of the American version of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), the remake of the film he had shot in Great Britain in 1934, showed there fails to describe how Hitchcock managed to unsettle viewers. By slow degrees the camera goes upstairs while Doris Day keeps singing her famous Whatever will be, will be, leaving clues to her son taken hostage. Much more than the linking of the shots we would need a handful of examples to understand better what mise en scène means. Either way, in the room labeled “Hitchcock and architecture” we may have a close look at the Edgar J Kaufman’s house inspired by the stunning Fallingwater house (1931) created by Frank Lloyd Wright. All those who have seen North by Northwest will remember the impressive mansion built upon a cliff.this respect the visitor should be sure

We all know that in Hitchcock’s films unforeseen circumstances may lead a law abiding citizen, most of time heedless of the danger he is in, to be handcuffed. Thanks to master Hitchcock he will go through the unlikeliest situations before finally being freed of anxiety. Our guilty pleasure is based on seeing how an innocent is forced to run for cover. A surprise awaits us at the beginning of the exhibition. It is noteworthy that in 1942, Stephen Early, Roosevelt’s press secretary commissioned Hitchcock to create a photo-novel about the danger of speaking to strangers in times of war. Somehow, according to the filmmaker, to walk leisurely around the corner may often put one at risk. To the point that when in a Hitchcock film a new character appears on the screen we ask ourselves: friend or foe?

The room labeled “Men and Women”, or shall I call it «kissing room», allows us to admire masterful moments in which Hitchcock indulged his impulse to capture displays of desire. Those excerpts belong to The Lodger (1926), Rear Window (1954), To catch a thief (1956), Vertigo (1958), the underrated but dazzling Marnie (1964).

It won’t be a disclosure to recall that he was married to Alma Reville for more than fifty years, nor is it a secret that the bald and fat director often fell under the spell of the achingly beautiful blondes he was eager to work with. What began being innocuous dalliance with some actresses morphed into deviant behaviour at the time he was shooting Marnie.

A reluctant Tippi Hedren underwent his underhanded wooing. For this sixty five year old man to spin out love’s sweet dream was already out of reach. The young actress softened the blow but for years this bad memory left her with a sour taste and she steered clear of him. (1) It is said that this catholic man obsessed by sins of commission and omission never led a riotous life. He solely committed himself with gusto to directing films. With women he showed reserve in the extreme, to such an extent that filmmaking bloomed into an opportunity to exert power over the world of make-believe where he would be in charge. On every account he felt a deep-seated need to control. The set in the studio was the best refuge ever known one in which dreams came true. Nonetheless, some actresses stated how horrid he was to them. For instance, Ingrid Bergman used to tell of the day she sought help from him because she felt unable to perform a scene of Notorious (1946) and didn’t feel that her character had a believable motivation, he answered: “Just pretend”.

According to the exhibit’s curator he sometimes behaved like a Pygmalion whose unwavering purpose consisted of converting actresses into idealized creatures. Nothing is truer but it would be stretching a point to say, as stated in the exhibition, that The Birds basically depicts the journey of the elegant Melanie from self-confidence to humiliation. Could we forget this mesmerising movie is first and foremost an epiphany?

Who better than Madeleine’s character in Vertigo embodies the aforementioned Pygmalion fantasy? Scottie (James Stewart) believes he has met Judy (Kim Novak) by sheer chance but does not know that she had been previously hired to be a false Madeleine. He wants Judy to look like Madeleine did before her faked death. He is yearning to dress Judy exactly as the so-called Madeleine did. His self-deception will unleash a tragic ending. As a matter of fact Hitchcock himself tried to check every single detail of Kim Novak’s hairstyle and manner of dress.

“Hitchcock and High Fashion” presents a light-hearted side of his filmography, let’s say the “Universal years” of the fifties. During this period it would have been inconceivable to include a bedraggled man or an unkempt in one his movies. On the contrary fancy and fashionable people, especially sophisticated ladies and somewhat mysterious, inspired by Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar magazines, happily lived in a world at peace. The sartorial elegance of the middle class concealed fears, wounds and madness. It is a real shame that none of the members of the dream team of those years is not mentioned. Nothing about the gorgeous cinematography of Robert Burks, Bernard Hermann’s haunting music, the brilliant graphic title sequences created by Saul Bass or the sharp editing done by George Tomasini. I would go so far as to say that the editing deserved a room by itself. Hitchcock’s mastery lies in no small part on editing because nothing is rushed within the mosaic of shots. In addition, who can deny after having seen one of his greatest films that editing has something to do with music? To the credit of the curator it has to be said that a workshop led in November by Teresa Font, a famous Spanish editor, will grant the happy few who will attend it the possibility to analyse the cutting and pace of some excerpts.

In short, the exhibition is worth visiting though the amateur won’t quench his thirst to know even more about how this devilishly clever man thought. A man able to blend entertainment, abstraction and art. Regardless, let’s not spoil our pleasure. The best is yet to come: to watch once again our favorites moments etched in memory.

(1) httpss://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/oct/31/tippi-hedren-alfred-hitchcock-sexually-assaulted-me