At first glance it may give the visitor a deceitful misgiving of misfortune, insofar as Munch felt unhinged since his youth, that led him from rushes of pleasure to collapses and nervous breakdowns. It is pointless to argue, as he acknowledged himself: “Illness, insanity and death were the black angels that watched over my cradle and accompanied me all my? life.” He could have stated as does the painter in Jean Renoir’s Port of Shadows (Le Quai des brumes, 1938): “When I see a swimmer I paint a drowned man” because he also saw “things behind things”, as if under the principal layer of painting a so-called pentimento would have revealed a darker but sharper vision, deep-rooted in a feeling blue attitude towards life until his dying day. And it’s fair to say he never wanted to marry and have children alleging that his blood and body were sick, if not rotten. However, he, the weakling of the family, the meekest of the meek, survived the nitty-gritty of life.

The self-taught painter was raised in Kristiania (known as Oslo since 1924) where the bush-league bourgeois, short-sighted by their puritan bias and their double-standard goodwill, tried to forbid conversations between profligate artists that were willing to plead for an untrammelled life and not to yield to the temptations, inasmuch the overall majority beggared by the oddities of life and weakened by alcohol, death wishes, syphilis and unsound mind knew they would not reach the age of forty. Sad and unbelievable as it may sound some were sorely in need of three daily meals to avoid the threat of starvation. Furthermore, most were doomed to fail or to search in exile an opportunity to be recognised. And Munch himself was compelled to try his luck first in Berlin an Paris.

The self-taught painter was raised in Kristiania (known as Oslo since 1924) where the bush-league bourgeois, short-sighted by their puritan bias and their double-standard goodwill, tried to forbid conversations between profligate artists that were willing to plead for an untrammelled life and not to yield to the temptations, inasmuch the overall majority beggared by the oddities of life and weakened by alcohol, death wishes, syphilis and unsound mind knew they would not reach the age of forty. Sad and unbelievable as it may sound some were sorely in need of three daily meals to avoid the threat of starvation. Furthermore, most were doomed to fail or to search in exile an opportunity to be recognised. And Munch himself was compelled to try his luck first in Berlin an Paris.

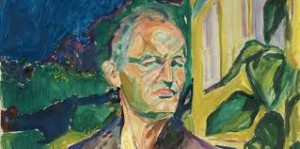

Regardless, he outclassed all of them and died at the age of eighty one, maybe inwardly spurred by the sheer necessity of voicing his talent at any price. The seamy side of life was to become the path where he would broaden his mind and find out the drawing force to keep on painting, in order to reach his vocational fulfilment. He didn’t seek admittance among the well-to-do society but waited for strokes of fortune that much later softened the blow of his former life. Indeed, for years the outcry was the only response he received from the self-righteous critics and the wealthy audience. Years after they shared a hushed silence about his work and much later on the utmost regard rewarded his whole life commitment. The Self-portrait in front of the House Wall (1926) shows a stout-of-build middle-aged man who seems to live far from wordliness. He could be a sailor or a woodcutter that no longer paints figures blurred by dusk. His face carved by time hides the suffering brought along by an eventful life. The eagle-eyed look underscores the unwavering willpower, akin to an out of bravado attitude. Nothing seems to escape his acumen.

It is known that the soul-stirring The Sick Child is inspired by the death of his sister Sophie whose passing, caused by tuberculosis, obsessed him to the point of doing a series of the same work from 1894 to 1907. What I favour in the main canvas is how our compassion grows in front of two persons overcome with grief, the girl who is about to die and her relative thunderstruck by the forthcoming bereavement. We, the unbeknownst viewers, attend a smooth and warm agony – should I say colourful?

It is known that the soul-stirring The Sick Child is inspired by the death of his sister Sophie whose passing, caused by tuberculosis, obsessed him to the point of doing a series of the same work from 1894 to 1907. What I favour in the main canvas is how our compassion grows in front of two persons overcome with grief, the girl who is about to die and her relative thunderstruck by the forthcoming bereavement. We, the unbeknownst viewers, attend a smooth and warm agony – should I say colourful?

Suffice it to say that the human figures painted by Munch usually remain still, silent, often alone, brooding over, staring at far places, and seldom look at each other, as if giving voice to emotions would be a daring challenge. Whether they seemingly look at us their statues’ gaze, vanishing into the void (Mother and daughter, 1897), or if they turn to the side emptiness dissolves their features (Laura and Inger in the summer sun, 1888). From Melancholy (1892) and The Storm (1893) to The Girls on the bridge (1933-35) and The Woman on the bridge (1934-40), painted almost a half century later, Munch underlines the loneliness of the ghostly figures. In those latter works instead of depicting a scene the painter enhances the rhythm of the stained colours crossed with lines by simplifying the picturesque atmosphere. In the landscapes that surround the characters no gust of wind or rain is barely shaping the petrified nature. The outer world appears as an unfathomable enigma, nor less are the inner sensations of the people who seem to be daydreamers on the brink of drifting. Munch said: “The long nocturnal hours with a thousand sinister thoughts until at last, at last morning came, then once again the long day, then once again the sleepless night.”

Fame came to him thanks to the misshapen faces he painted in his early thirties (Angst, 1896, Panic). He was contemporary of the dominant expressionist traits prone to describe the wincing carnival of living corpses. It is regretful because he also attempted to embrace life and death together. As he said: “When I paint illness and misfortune it is on the contrary a healthy release. It is a healthy reaction that one can learn from and live by.”

Fame came to him thanks to the misshapen faces he painted in his early thirties (Angst, 1896, Panic). He was contemporary of the dominant expressionist traits prone to describe the wincing carnival of living corpses. It is regretful because he also attempted to embrace life and death together. As he said: “When I paint illness and misfortune it is on the contrary a healthy release. It is a healthy reaction that one can learn from and live by.”

In sober truth, if we have time in our hands, we will guess below the imprints of the paintings a stream of strength that emerges from despair and morphs into a spring of life. Deep inside, Munch thought: “Up from my rotting carcass flowers shall spring up and I shall be in them. Eternity” That puts a different shine on his work, widely regarded as being nurtured by anxiety and tainted with sadness. To some extent a world-weary man’s blood turns into a bold new energy. This reminds me of the famous William Faulkner’s sentence that we read in The Wild Palms : “Given a choice, between grief and nothing, I’d choose grief”

For many people Munch is basically the author of the hugely famous The Scream (1895). Was it a breakthrough? Perhaps but for my liking it is nowhere near as good as Adam and Eve (1919) wherein the man and the woman are waiting with relish for the blooming desire that either way is about to grow, so that at both sides of the Tree of life in the spring-like garden the two youngsters, maybe peasants, are the heirs of an endless tale that soon will be told again. Rather than telling the erotic climax of the love story Munch prefers a hanging ending.

At the core of his artistic creation stands the woman. I am tempted to believe he felt intoxicated with women’s kisses, fragrances and the brazen joy of sharing feverish pleasure. Madonna (1892) and Woman with red hair and green eyes: sin (1902) verge on symbolism charged with religious connotations since the woman is here a holy haunting sinner, a spellbinding beauty that embodies at the same time Heaven and Hell. According to him: “I have lived in the age of transition in the midst of the emancipation of women. Then it was the woman who seduced and lured and betrayed the man. The age of Carmen. In the age of transition man became the weaker sex.”

At the core of his artistic creation stands the woman. I am tempted to believe he felt intoxicated with women’s kisses, fragrances and the brazen joy of sharing feverish pleasure. Madonna (1892) and Woman with red hair and green eyes: sin (1902) verge on symbolism charged with religious connotations since the woman is here a holy haunting sinner, a spellbinding beauty that embodies at the same time Heaven and Hell. According to him: “I have lived in the age of transition in the midst of the emancipation of women. Then it was the woman who seduced and lured and betrayed the man. The age of Carmen. In the age of transition man became the weaker sex.”

An overflowing obsession runs through the variations about The Kiss (1894-1917) and Vampire (1916-1918). Man and woman open the gates to a passionate bond that leads them to the edge of a lasting lust. Though Munch claimed he only wanted to paint a kiss whoever watches the series called Vampire is entitled to think such a woman is a gorgeous goddess or a witch. It reminds us of how often woman was somewhat idealized or feared.

What awaits us in the last room is some of the towering achievements exhibited in the Thyssen Museum, I mean the nudes titled Weeping Nude (1913-1914), Kneeling Woman (1919) and above all Model by the wicker chair (1919-1921). Their lively nakedness offers us a blend of blissful sigh, whisper, weep and pride too. In the two first paintings the unvarnished vision of doleful solitude is balanced by a respectful insight. We know nothing about the hardships that tear apart the weeping and the kneeling women, we are just witnessing their pain, beyond any kind of voyeurism. Quite different is the third painting: here it is an acute vision of sensual flesh at last stripped off moral preconceptions. Actually, her nodding head tells us our benevolence and patience will strengthen her peace and quiet confidence.

What awaits us in the last room is some of the towering achievements exhibited in the Thyssen Museum, I mean the nudes titled Weeping Nude (1913-1914), Kneeling Woman (1919) and above all Model by the wicker chair (1919-1921). Their lively nakedness offers us a blend of blissful sigh, whisper, weep and pride too. In the two first paintings the unvarnished vision of doleful solitude is balanced by a respectful insight. We know nothing about the hardships that tear apart the weeping and the kneeling women, we are just witnessing their pain, beyond any kind of voyeurism. Quite different is the third painting: here it is an acute vision of sensual flesh at last stripped off moral preconceptions. Actually, her nodding head tells us our benevolence and patience will strengthen her peace and quiet confidence.