Literary fiction “fell on me” without even experiencing a “vocation.” I had no choice but to write to free myself from what was sprouting inside me. Until then, I was a happy reader. Since then, if a book captivates me, the enjoyment is enhanced, but if I dislike it, my boredom, discouragement, or anger are much greater.

It is difficult to describe such an activity idealized by those who do not know it. Joseph Conrad was right when he said: “My wife does not understand that I am working when I look out the window.”

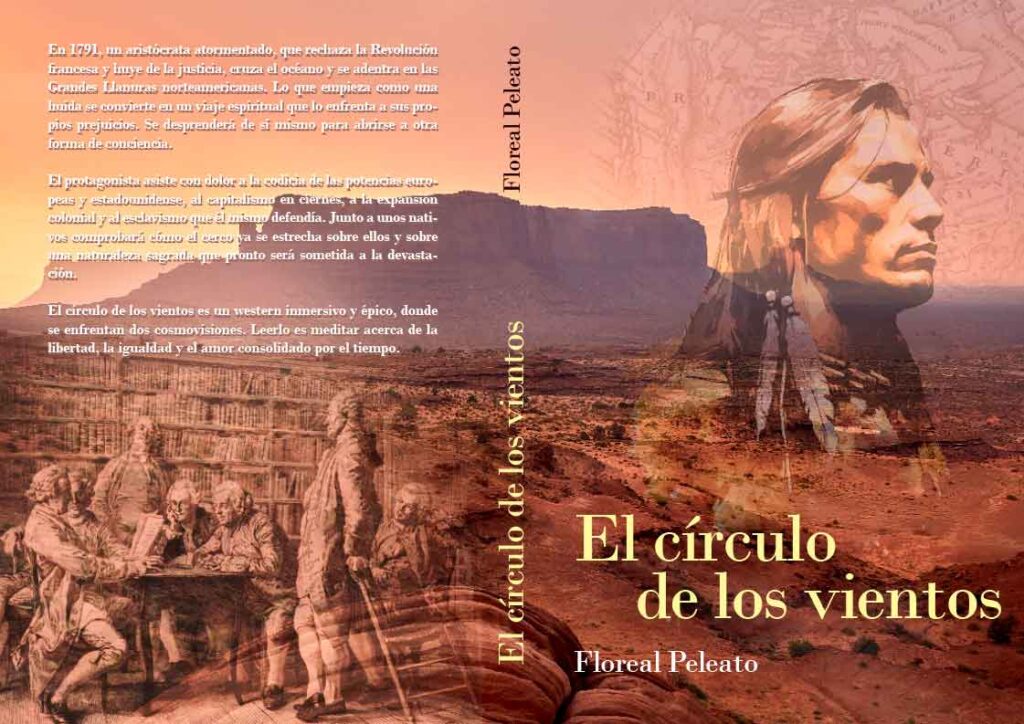

I started by writing short stories, some of which were collected in a book (Seven Voices), and then I returned to a long-winded story, deeply rooted and of slow emergence. The writing process was consolidated thanks to numerous historical, and I don’t know whether to call them anthropological, readings, to give birth to the novel entitled The Circle of the Winds set between 1791 and 1806 in the Great Plains of the United States.

On the other hand, without knowing how, step by step, I wrote more than fifty articles published in the film magazine Positif.

Synopsis:

In 1791, a tormented aristocrat, who rejects the French Revolution and flees from justice, crosses the ocean and enters the Great North American Plains. What begins as a flight becomes a spiritual journey that confronts him with his own prejudices. During the journey, he will detach himself to open himself to another form of consciousness.

The protagonist painfully witnesses the greed of the European and American powers, the nascent capitalism, the colonial expansion, and the slavery that he himself defended. Together with some natives, he will see how the siege is already tightening on them and on a sacred nature that will soon be subjected to devastation.

The Circle of the Winds is an immersive and epic western where two worldviews collide. Reading it is meditating about freedom, equality, and love consolidated by time.

Synopsis:

In Seven Voices, the narrator’s voice is stripped away so that his characters live in the first person. He had to find for these stories the thoughts and feelings of men and women of very different ages, social, geographical, and historical backgrounds. To reach the affective nakedness that reveals the deepest emotions, it was important to trust introspection, thanks to which the characters affirm their vitality in spite of the wounds. In the search for all of them, a certain tension towards the ideal, the fragile, and the primeval emerges. In Seven Voices “all voices, be they untuned voices, voices shrouded in fear, haughty voices, broken by emotion, harsh or cheerful, all voices merge into a musical matrix.

The attached PDF contains Seven Photos and Dear Victor. These two monologues are part of the seven stories gathered in Seven Voices.

The screenwriter and director in me is drawn to character-driven stories, scripts that avoid dramatic acrobatics, formal adventures, openness to the imaginary, and auteur cinema expressed within established genres.

At the start of my projects, a matrix image and a character emerge, never a plot or a theme. I discover them later once the characters gain strength. I can only write what I visualize, which is why I consider myself more of a screenwriter-director than a pure screenwriter.

My stories can be set here and now, in distant countries, long ago, or in the near future; all of them, according to the professionals who have read them, stand out for their brevity and sobriety, for their contained dramatic intensity, and for a certain lyricism.

I tend to rewrite the sequenced treatment a lot. As Hitchcock said, “Once the script is written, all that remains is to add the dialogue.” Of course, it worked in his case, but not all screenwriters and directors have the same needs.

As long as the foundations are not solid for me, it makes no sense to write a dialogued continuity. Unlike many authors, I do not advocate writing many versions of the script. An “overwritten” script leaves less space for staging, to the point that sometimes the films are mere filmed scripts.

Years ago, I read something in Elia Kazan’s copious autobiography that caught my attention. The filmmaker, who had read the original manuscripts and typescripts of playwrights on their way to fame (Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Clifford Oddets, William Inge), came to the following conclusion: “when a play is good, it is good from the start.” Until then, I naively believed in the infinite powers of rewriting. For some time now, I have shared Kazan’s conviction.

I have discovered that in my case, one must not seek but wait. If I search eagerly, it is a futile effort produced by a rational will that inhibits. When the contours of the story, its structure, and above all its tone and rhythm, finally take shape, the work becomes intense and the course, clear.

As an author, I observe changes in my work. Increasingly, the implicit montage of the scenes guides my way of constructing them. On the other hand, in the most recent scripts, women and ecological reflection are protagonists. Although I live in a large city, it is usually nature that inspires me, the city very rarely.

My scripts have been selected to participate in workshops or meetings such as Madrid CreaLab, Casa de América, Equinoxe, la Maison des Scénaristes, the SGAE, the online market of the Cannes festival, or Cinenido.

The time has come to turn them into films.

DUELLISTES Nº 548, octobre 2006, p 97-98. Depuis le Grand

MYSTERE DE LA DOUCEUR Positif, nº 565, mars 2008, p

SIERRA DE TERUEL, ÉLÉGIE POUR UNE RÉPUBLIQUE DÉFUNTE Positif, nº

LA MUSIQUE SILENCIEUSE DU GESTE Biographies de peintres à l’écran

Pocas veces un director ha propuesto tantas maneras de mostrar la pintura en el cine: citas, «tableaux vivants», artista frente a su obra, desfile de lienzos en un pasillo de la memoria, pesadillas. Todo ello con el fin de sumergirnos en parte solamente en la mente poderosa de Goya. En este texto trato de comprender los pasos seguidos por Carlos Saura para hilvanar un relato poco conforme con las estructuras habituales para dar rienda suelta a su creatividad y de establecer filiaciones y diferencias con otras muestras de «cine y pintura».

Artículo publicado en el nº 624 de Positif en febrero

Artículo publicado en la revista Positif (nº 737-38, julio-agosto de

Algunos apuntes acerca de la relación en el cine contemporáneo entre voz y erotismo.

Una reflexión sobre el “amor loco” o cuando enloquece los personajes de Claude Chabrol se sienten cautivos e impulsados a cometer “locuras”.

Artículo dedicado a Sidney Lumet, publicado en el nº 575

Artículo publicado en enúmero doble de julio/agosto de 2007 (nº

A propósito de seis películas de Buñuel que no todas se encuentran entre sus más conocidas.

Michael Cimino said that literature generates thoughts and cinema sensations and feelings. I think I understand the filmmaker’s conviction and I share it. If a film provokes reflection, welcome it, but it can be awakened by a look, a gesture, a voice, a light effect, a musical fragment, or a sound.

From my point of view, the literary work immerses us in a journey, which we can undertake again at our whim, when the script condemns us to remain in a frustrating threshold.

If there is style in a script, it must be perceived in the tone, in the tempo, and even more so in the gaps in the story, necessary for the promise of a film to be fulfilled. It is still a score, of ungrateful reading, that does not come to life until it is interpreted.

With regard to writing articles, they help me to clarify my reflections on cinema, although I dedicate too much time to shaping and pacing them.