My first cinematic pleasures were provided by films programmed on television, but sometimes my parents sent me to bed early, too early for my liking. By listening to films from the bedroom, I discovered the so-called “off” space.

During my childhood, I enjoyed watching film noir and comedies, among which the most exhilarating antidote to sadness I know: Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952). Without a doubt, “Good mornin’” can soften any underlying hint of melancholy.

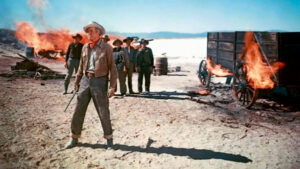

At that time, my favorite genre was the western. I did not know then that some of my favorite westerns had been directed by Anthony Mann. Years later, his framing, his leisurely tempo, and his dramatic concision seemed to me of an unusual expressive force.

I was very moved by The Miracle Worker (Arthur Penn, 1962). I was twelve years old. It made me feel that cinema could provide almost epidermal emotions without addressing the intellect. And I had the impression that through access to language, Helen Keller, the deaf-blind girl, was born for the second time.

Far Country (Anthony Mann, 1954)

The Man from Laramie (Anthony Mann, 1955)

The Miracle Worker

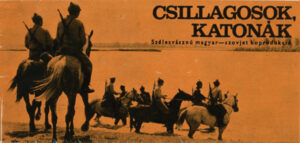

At the same age, one day returning from school I saw The Red and the White (Csillagosok, Katonák, Miklós Jancsó, 1967), set during the First World War in the Hungarian Puszta. It seemed like a rarity to me, I didn’t understand anything but, despite its coldness, I was captivated by the choreography of its camera movements. I didn’t know they were called sequence shots.

And Jancsó employed here one of the most beautiful visual combinations imaginable: the scope format in black and white. Robert Rossen made that same choice to enhance the drama in The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961) which, shortly after, I liked so much.

A couple of years later I saw Marnie (Alfred Hitchcock, 1964) in front of which I perceived that the camera and color allowed us to explore some disturbing areas of our being, until reaching something whose name I did not know: the unconscious. In addition, for the first time the subtitled original version allowed me to savor a concert of voices in a different language.

While my relatives slept, the original version, listened to with low volume, became a repeated clandestine pleasure, thanks to the programming of the Ciné Club of Antenne 2 and the Cinéma de Minuit of FR 3. Yes, then I lived in France. Memorable for me was the television screening of The Music Room (Jalsaghar, Satyajit Ray, 1958), three or four years later. Under the gaze of the Bengali filmmaker, whose name I did not even know, the hypnotic passage of time anesthetized reason and the everyday was charged with sensuality.

The Hustler

White Mane

Jalsaghar

The Red and the White

Very sensory was also a medium-length film that I saw when I was nine years old, I think, in the schoolyard, while it was raining: White Mane (Crin Blanc, Albert Lamorisse, 1953). I forgot it for many years, although I suppose I must have identified with the young Folco capable of riding the indomitable thoroughbred in the dunes of Camargue.

If I have learned anything with respect to the notion of mise en scène it is because I had the fortune to see The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock, 1963) at thirteen years old. My admiration for that audacious epiphany, fortunately devoid of rational explanation, bordering on the abstract and seasoned with suspense, has never diminished.

Then I saw A Man Escaped (Un condamné à mort s’est échappé, Robert Bresson, 1956). The truth is, I don’t remember what I felt in the face of the edge of such cutting artistic control, although the sound space and the ellipses merged in a miraculous way into a mosaic of very fragmented planes.

During adolescence I began to see many films on the big screen. Among the deepest shocks are ten or fifteen American films, harsh and vital, shot during the seventies. I was also fascinated by the mineralization of the world filmed by Antonioni, the frescoes of Visconti and his pictorial use of color. And some female faces left an indelible mark, no less than their silhouettes and their voices.

The Birds

A Man Escaped

Days of Heaven

Andrei Rublev

Among all those important films in my dawning memory as a spectator, I would like to highlight two: Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 1978) and Tabu (F W Murnau, 1931), the first sparse in words, the second silent, both lyrical and set in an all-powerful nature.

But above all I must place Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1967), seen by chance just after turning seventeen. Suffice it to say that my life as a spectator took a turn and that I still consider the last episode of Tarkovsky’s film (the casting of the bell) one of the most beautiful moments in the history of cinema.

Afterwards, I tried to allow myself time to know and understand the cinema.

And then I started writing and filming…